北欧绿色邮报网报道(记者陈雪霏)--4月出,本网记者因采访报道祭奠轩辕黄帝陵而到西安。期间参观了西安市容市貌,虽然说那里雾霾也比较严重,但毕竟还是纬度朝南,江南景象常现。

这里是步行街,仿佛王府井的步行文化街。电影城。

艺术家们用心良苦。

镜头里的西安大雁塔。 全部图片由陈雪霏拍摄。

STOCKHOLM, Dec. 7 (Xinhua) — Artemisinin, the most effective drug that combat malaria today is “a gift from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to the world”, said Tu Youyou, in her presentation at Nobel Lectures in Physiology or Medicine in Stockholm on Monday.

In the half-hour-long lecture at Karolinska Institutet in central Stockholm with full participation of a thousand audience, Tu detailed a vivid story in the 1970s of how a group of Chinese researchers despite various challenges successfully developed a cure to treat malaria.

In the half-hour-long lecture at Karolinska Institutet in central Stockholm with full participation of a thousand audience, Tu detailed a vivid story in the 1970s of how a group of Chinese researchers despite various challenges successfully developed a cure to treat malaria.

Tu won 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discoveries concerning a novel therapy against Malaria, artemisinin.

Drawn from valuable research experiences in developing artemisinin, Tu believes “Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure-house”, which “should be explored and raised to a higher level.”

“Since ‘tasting hundred herbs by Shen Nong’, China has accumulated substantial experience in clinical practice, integrated and summarized medical application of most nature resource over the last thousands of years through Chinese medicine,” Tu said.

“Adopting, exploring, developing and advancing these practices would allow us to discover more novel medicines beneficial to the world healthcare,” Tu stressed.

“The sun along the mountain bows; The Yellow River seawards flows; You will enjoy a grander sight; By climbing to a greater height!” Tu quoted a poem from China’s Tang Dynasty in her speech.

“Let’s reach to a greater height to appreciate Chinese culture and find the beauty and treasure in the territory of traditional Chinese medicine!” She said.

“I enjoyed it very much, it’s fascinating story when she recalled how she went back to TCM and found this method that’s so very important for mankind,” Lars Heikensten of the Nobel Foundation told Xinhua, “it’s truly enjoyable moment.”

“I enjoyed it very much, it’s fascinating story when she recalled how she went back to TCM and found this method that’s so very important for mankind,” Lars Heikensten of the Nobel Foundation told Xinhua, “it’s truly enjoyable moment.”

Despite Tu presented in Chinese and had her English version in PPT on background screen, Jan Lindsten, emeritus professor and former Secretary-General of Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine, understood and enjoyed very well.

“She made a very mature comparison between modern pharmacology and Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), which I think is extremely important and well worth to pursue in future to find treasure from TCM in developing new drugs,” Lindsten told Xinhua.

“I am quite sure we will have future medicine comes from nature!” Birgitta Rigler, head of the Rehabilitation Clinic in Dandryd’s Hospital in Stockholm, told Xinhua.

“Chemical industry may be faster in developing new drugs, but perhaps nature-based things are more durable,” she said. Enditem

BEIJING, Dec. 8 (Xinhua) — To ensure a medium-high level of economic growth for the next five years, China has moved to foster new growth engines as old ones lose steam.

China’s exports dropped by 3.7 percent in November, the fifth straight month of decline, to 1.25 trillion yuan (195 million U.S. dollars), customs data showed Tuesday.

In recent years, old growth engines, including exports and investment, lost momentum partly due to weak demand at home and overseas. The country’s quarterly GDP growth slowed to a six-year low of 6.9 percent in the third quarter of this year.

In the next five years, the country’s annual growth rate should be no less than 6.5 percent to realize the goal of doubling the GDP and per capita income of 2010 by 2020.

To attain that goal, the government must cultivate new growth engines to bolster growth in the next five years.

EMERGING INDUSTRIES

As traditional industries including steel, coal and cement sectors are facing excessive capacity, China is moving to tap the potential of new industries with bright prospects.

A proposal for formulating the country’s 13th five-year plan unveiled last month said that China will step up researches on core technology concerning the new generation of telecommunications, new energy, new material and aviation, and support the development of new industries, including energy conservation, biotechnology and information technology sectors.

In Changzhou, a city in eastern China’s Jiangsu Province, there are more than 50 companies producing graphene, a new material that widely used in high-end equipment manufacturing, forming a national level production base for the material. Products made by Changzhou Tanyuan Technology Co. are used in smartphones. The company’s sales have risen from 6 million yuan to more than 200 million yuan in only three years.

Qi Chengyuan, head of the high-tech division of the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), said China will turn new strategic industries into major driving forces for economic growth in the next five years.

The country should form five new pillar industries that each have a potential of becoming a 10 trillion yuan industry, including information technology, bioindustry, green industry, high-end equipment and material, as well as the creative industry, Qi said.

ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND INNOVATION

New impetus must also come from the government’s emphasis on mass entrepreneurship and innovation.

In the first three quarters, China’s newly registered companies rose 19.3 percent to 3.16 million, as the country pushed for easier registration to promote innovation.

Innovation is the most important impetus for China’s growth, according to the proposal for formulating the 13th five-year plan.

A good example is the strong growth in Shenzhen, a national demonstration zone for independent innovation. In the first 10 months, the proportion of R&D investment in Shenzhen’s regional GDP was more than 4 percent, nearly doubles the national average.

The city’s economic growth stood at 8.7 percent in the first three quarters, higher than the country’s growth of 6.9 percent in the same period.

The Shenzhen-based Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. has set up 16 overseas R&D institutions and owns a total of 76,687 patents, said its CEO Ren Zhengfei.

The Shenzhen-based Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. has set up 16 overseas R&D institutions and owns a total of 76,687 patents, said its CEO Ren Zhengfei.

The company realized a sales volume of 288 billion yuan last year. Ren forecast that the company will more than double that sales figure by 2019 on the back of constant innovation.

Song Weiguo, researcher with the Chinese Academy of Science and Technology for Development, said that technological innovation will provide greater impetus for growth in the next five years.

REFORMS ON SUPPLY SIDE

Structural reforms on the supply side will lend more steam to sustainable growth, President Xi Jinping said last month at a meeting of the Central Leading Group for Financial and Economic Affairs.

Xu Lin, head of the NDRC’s planning division, said reforms on the supply side, which means sustainable growth instead of short-term demand management, is necessary for cultivating new growth impetus.

An important aspect of supply side reforms is government efforts to streamlining administrative approvals and delegating power to lower levels.

From early 2013 to the end of September 2015, the central government has canceled or delegated 586 kinds of administrative approval.

In the economic and technological development zone of Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, the bureau in charge of administrative approvals cut the red tape and reduced the time needed for getting an approval from more than 300 days to 20 days.

On the supply side, China should maintain structural tax reductions to boost the service and advanced manufacturing sectors and support small enterprises, and push forward entrepreneurship and innovation, Premier Li Keqiang said earlier this month.

China will keep cutting red tape to foster emerging industries and speed up the overhaul in traditional industries to improve efficiency, Li said.

With new impetus from China’s reform pushes, the country will be able to realize an average annual growth of 6.5 percent in the next five years, said Yu Bin, researcher with the Development Research Center of the State Council. Enditem

BEIJING, Dec. 11 (Xinhua) — Nearly 20 provincial governments in China have rolled out their local development plans for the 13th Five Year Plan period from 2016 to 2020, with their focus on the “Belt and Road” construction, the Shanghai Securities News reported on Friday.

Under their development plans, they attach great importance to infrastructure construction in transportation industry and construction of industrial parks.

— Focus on transport infrastructure

Chinese local governments will give priority to transport infrastructure when promoting the “Belt and Road” initiative.

For example, Shaanxi province will be guide by construction of a logistics center to build a seamless transport network in 2016-2020. Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region also said in its proposal to the 13th Five Year plan that it will build a convenient and efficient railway network, expressway network, water transport network, airline network and information network with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and neighboring provinces.

It is worth noting that in the land transportation field, the China-Europe express railway will play an increasingly important role in “going global” of Chinese goods.

As a core area of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, Fujian province plans to build important airline hubs for Southeast Asia and advance construction of a regional port-shipping system and communication network facilities, to smoothly connect the land channel of the Silk Road Economic Belt and form a passage to sea for central and western China’s opening-up.

Jilin province in its 13th Five Year plan noted that it will actively explore the Arctic Ocean ship routes linking the Europe and the U.S.A., steadily operate international rail and water transportation lines linking Japan and South Korea, and further expand its outward transport lines.

Meanwhile, Tianjin will make full use of its unique geographic location advantages to vigorously promote port and maritime strategic cooperation. It will develop cross-border logistics through three land ports, like the Khorgos Port and develop maritime transport through intensive ship routes and shipping flights.

Zhejiang province announced to promote construction of a marine economic development demonstration zone and Zhoushan Islands New Area, and build a port economic circle covering the Yangtze River Delta, influencing the Yangtze River economic belt and serving the “Belt and Road” initiative.

In addition, Gansu province decided to invest more than 800 billion yuan from this year to build more than 70,000 km of roads and railways in six years.

— Efforts in industrial park construction

Industrial park construction is also a focus in the 13th Five Year plans of the provinces.

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region said that it will accelerate construction of core areas in the Silk Road Economic Belt, develop high-level open economy, and quicken the pace to build the Kashgar and Khorgos economic development zones and comprehensive bonded zones.

Because of the “Belt and Road” initiative, ALaShankou has invested a lot in infrastructure, promoting rapid development of its comprehensive bonded zone, said Pan Zeming, deputy director of the ALaShankou Comprehensive Bonded Zone.

In its 13th Five Year plan, Fujian province made it clear to promote construction of important commodity export bases, commodity markets and commerce and trade parks and explore mutual establishment of industrial parks with Southeast Asian countries.

Chongqing municipality pointed out that it will actively participate in construction of overseas industrial agglomerations and economic and trade cooperation zones.

Shaanxi province said it will encourage and support competent enterprises to go abroad for transnational operation and strategic acquisitions and build Shaanxi industrial parks overseas especially in Central Asia and Africa. Meanwhile, it will also build economic cooperation zones and high-tech industrial parks to attract investments of the transnational companies and globally leading enterprises and persuade them to build regional headquarters and branches in Shaanxi.

“Industrial park is an important method for “going global” of Chinese enterprises. It is a new form for Chinese enterprises to build “Belt and Road” and also a way to change simple cargo transportation”, said Hu Zheng, chief representative of the Central Asia Representative Office of the China Merchants Group.

Since the beginning of the year, China has quickened its pace of building industrial parks along the “Belt and Road” countries.

Data of the Ministry of Commerce shows that so far, China has already built 118 economic and trade cooperation zones in 50 countries, of which 77 zones are located in 23 countries along the “Belt and Road”. Enditem

BEIJING, Dec. 11 (Xinhua) — With China’s 13th Five-year Plan beginning next year, the focus of reform will start with addressing the quality of ordinary people’s lives.

At the latest meeting of the central leading group for comprehensively deepening reform on Wednesday, the leadership decided to implement the five development ideas put forward at the plenary session of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee in late October: innovation, coordination, sharing, environmental protection and openness.

At the beginning of the 13th Five-year Plan, efforts need to be “focused on building a moderately prosperous society,” said a statement issued after Wednesday’s meeting.

The group approved several reform measures, one of which is that unregistered citizens are to be given household registration permits known as “hukou,” a crucial document entitling them to social welfare.

China has around 13 million unregistered people, one percent of the entire population. They include orphans and second children born illegally during the period of strict enforcement of the one-child policy, the homeless and those who have yet to apply for one or who have simply lost theirs. Those parents who violated family planning policy often refrained from getting hukou for their children to avoid fines.0 “It is a basic legal right for Chinese citizens to register for hukou. It is also a premise for participation in social affairs, to enjoy rights and fulfill duties,” the statement said.

Wan Haiyuan with an institute of macro-economics of the National Development and Reform Commission said the difficulty lies not in hukou itself, but in related matters such as healthcare, health insurance and education.

In China, various social benefits such as medical insurance and access to basic education are based on this permit and are supposed to be in line with long-term places of work and residence.

Many people without household registration have moved to cities and become tramps. According to Wan, their birth certificates might have been lost and authorities must address this issue. Those who have come to China to seek asylum should also be taken into consideration, as they are permanent residents, despite their lack of Chinese nationality.

Education is also central to plans for the next five years, said Zhang Li, director of the Ministry of Education’s development center. The reform meeting statement declared that education should advance innovation-driven development and serve the objectives of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Zhang added the statement showed that opening up in education should take the concepts and experience of developed countries as reference.

The meeting decided to integrate basic medical insurance for urban employees and the new rural cooperative medical scheme, creating a unified basic health insurance system.

Currently China has three separate medical insurance schemes — basic medical insurance for urban employees; the new rural cooperative medical scheme; and basic medical insurance for city dwellers not covered by the first two schemes, mainly the young or unemployed.

The three schemes have been perceived as unequal for a long time, as the benefits in urban areas are much greater than those in rural parts of the country.

“Even members in one family may have different health insurance,” said Meng Qingyue, a professor in health economics with the Peking University. “The integration of different medical insurance schemes is a must for achieving equal access to basic health care for every one.”

Another measure is the reform of government’s “power list.” Since the 18th National Congress of the CPC in late 2012, administrative powers have been streamlined and delegated, with hundreds of items abandoned.

Ma Qingyu of the Chinese Academy of Governance said the power and responsibility list system can clarify responsibilities of different departments and prevent them from shirking their responsibilities or taking responsibilities that are not rightfully theirs.

“It will make the border between public powers and private rights more clear,” said Ma. Enditem

Stockholm, Dec. 15(Greenpost)– Chinese Nobel Laureate in Medicine Tu Youyou gave a wonderful Nobel Lecture in the Aula at Karolinska Institute on Dec. 7, 2015 in Chinese. But with English text. The following is the whole text in English:

Tu Youyou’s Nobel Lecture.

2015-12-07

Dear respected Chairman, General Secretary, esteemed Nobel Laureates, Ladies and Gentlemen:

It’s my great honor to give this lecture today at Karolinska Institutet. The title of my presentation is Artemisinin-A Gift from Traditional Chinese Medicine to the World.

Before I start, I would like to thank the Nobel Assembly and the Nobel Foundation for awarding me the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This is not only the honor for myself, but also the recognition of and motivation for all scientists in China. I would also like to express my sincere appreciation to the great hospitality of the Swedish people which I have received during my short stay over last few days.

Thanks to Dr. William Campbell and Dr. Satoshi Ömura for the excellent and inspiring presenations. The story I will tell today is about the dilligence and dedicaiton of Chinese scientists during searching for antimalarial drugs from the traditional Chinese medicine forty years ago under considerably under-resourced research conditions.

Discovery of Artemisinin

Some of you may have read the history of artemisinin discovery in numerous publications. I will give a brief review here. This slide summerizes the antimalarial research program carried out by the team at the Institute of Chinese Malaria Medica(ICMM) of Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine(ATCM) in which the programs highlighted in blue were accomplished by the team at ATCM while the program highlighted with blue and white were completed through joint efforts by the teams at ATCM and other institutes. The un-highlighted programs were completed collaboratively by the other research teams across the nation.

Discovery of Artemisinin at ICMM

The team at ICMM initiated research on the Chinese Medicines for malaria treatment in 1969. Following substantial screening, we started to focus on herb Qinghao in 1971, but received no promising results after multiple attempts. In September 1971, a modified procedure was designed to reduce the extraction temperature by immersing or distilling Qinghao using ethyl ether. The obtained extracts were then treated with an alkaline solution to remove acidic impurities and retain the natural portion.

In the experiments carried out on October 4th 1971, sample No. 191 i.e. the neutral portion of the Qinghao ether extract was found 100% effective on the malaria mice when administered orally at a dose of 1.0g/kg for consecutive three days. The same results were observed when tested in malaria monkeys between December 1971 and January 1972. This breakthrough finding became a critical step in the discovery of artenisinin.

We subsequently carried out a clinical trial between August and October 1972 in Hainan province in which the neutral Qinghao ether extract successfully cured thirty falciparum and plasmodium malaria patients. This was the first time the neutral Qinghao ether extract was tested in human. In November 1972, an effective antimalarial compound was isolated from the neutral Qinghao Ether extract. The compound was late named Qinghaosu(artemisinin in Chinese).

Artemisinin Chemistry Studies

We started to determine chemical structure of artemisinin in December 1972 through elemental analysis, spectrophotometry, mass spectrum, plarimetric analysis and other techniques. These experiements confirmed that the compound had a complete new sesquiterpene structure with a formula of C15H22O5, a molecular weight of 282 and contained no nitrogen.

Stereo Structure of Artemisinin

The formula of the molecule and other results were verified by the analytical chemistry department of China Academy of Medical Sciences on April 27th 1973. We started collaboration with Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry and the Institute of Biophysics of Chinese Academy of Sciences on artemisinin chemical structure analysis in 1974. The stereo-structure was finally determined using the X-ray diffraction technique which verified that artemisinin was a new sesquiterpene lactone containing a peroxy group. The structure was published in 1977 and cited by the Chemical Abstracts.

Artemisinin and Artemisinin Derivatives

Derivatization of artemisinin was performed in 1973 in order to determine its functional group. A carboxyl group was verified in the artemisinin molecule through reduction by sodium borohydride. Dihydroartemisinin was found in this process. Further research on the structure-activity relationship of artemisinin was conducted. The peroxyl group in the artemisinin molecule was proven critical for its antimalarial function. Efficacy was improved for some compounds derivatized through the hydroxy group of dihydroartemisinin.

Artemisinin and Artemisinin Derivatives

This slide shows the chemical structures of artemisinin and its derivatives –dihydroartemisinin, artemether, artesunate, arteether. Up to now, no clinical application has been reported with other artemisinin derivatives except for the four presented here.

Artemisinin and Dihydroartemisinin New Drug Certificates

This slide shows the Artemisinin New Drug Certificate and the Dihydroartemisinin New Drug Certificate(right) granted by the China Ministry of Health in 1986 and 1992, respectively. Dihydroartemisinin is ten times more potent than artemisinin, again demonstrated ”high efficacy, rapid action and low toxicity” of the drugs in the artemisinin category.

Worldwide Attention to Artemisinin

The World Health Organization(WHO), the World Bank and United Nations Development Program(UNDP) held the 4th joint Malaria Chemotherapy Science Working Group meeting in Beijing in 1981. A series of presentations on artemisinin and its clinical application including my report”Studies on the Chemistry of Qinghaosu” received positive and enthusiastic responses. In the 1980s, several thousand of malaria patients were successfully treated with artemisinin and its derivatives in China.

After this brief review, you may comment that this is no more than an ordinary drug discovery process. However, it was not a simple and easy journey in discovery of the artemisinin from Qinghao, a Chinese herb medicine with over two thousand year clinical application.

Commitement to the Clearly Defined Goal Assures Success in Discovery

The Institute of Chinese Materia Medica of Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine joined the national ”523” anti-malaria research project in 1969. I was appointed the head to build the ”523” research group in the institute by the academy’s leadership team, responsible for developing new antimalarial drugs from Chinese medicines. It was a confidential military program with a high priority. As a young scientist in her early career life, I felt overwhelmed by the trust and responsibility received for such a challenging and critically important task. I had no choice but fully devoted myself to accomplishing my duties.

Knowledge is Prologue in Discovery

This is a photo taken soon after I joined the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica. Professor Lou Zhiqin(left), a famous pharmacognosist, was mentoring on how to differentiate herbs. I attended a training course on theories and practices of traditional Chines medicine designed for professionals with a modern(western ) medicine training background. ”Fortune favors the prepared mind”1 and ”What’s past is prologue.”2 My prologue of integrated training in the modern and Chinese medicines prepared me for the challenges when the opportunities in searching for antimalarial Chinese medicine became available.

Information Collating and Accurate Deciphering Are the Foundation for the Success in Research

After accepting the tasks, I collected over 2000 herbal, animal and mineral prescriptions for either internal or external uses through reviewing ancient traditional Chinese medical literatures and folk recipes, interviewing those well-known experienced Chinese medical doctors who provided me prescriptions and herbal recipes. I summarized 640 prescriptions in a brochure ”Antimalarial Collections of Recipes and Prescriptions.” It was the information collection and deciphering that laid sound foundation for the discovery of artemisinin. This also differntiates the approaches taken by Chiense Medicine and general phytochemistry in searching for novel drugs.

Thorough Literature Reviewing Inspires an idea leading to Success

I reviewed the traditional Chinese literatures again when our research stalled following numerous failures. In reading Ge Hong’s ”A Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies,” (East Jin Dynasty). 3rd-4th century). I further digested the sentence”A Handful of Qinghao Immersed in Two Liters of Water, wring out the Juice and Drink It All” when Qinghao was mentioned for alleviating the malaria symptoms. This reminded me that the heating might need to be avoided during extraction, therefore the method was modified by using the solvent with a low boiling point.

The earliest mentioning of Qinghao’s application as a herbal medicine was found on the silk manuscripts entitled ”Prescriptions for Fifty-two Kinds of Disease” unearthed from the third Han Tomb at Mawangduei. Its medical applicaiton was also recorded in ”Shen Nong’s Herbal Classic”, ”Bu Yi Lei Gong Bao Zhi” and ”Compendium of Materia Medica”, etc. However, no clear classification was given for the Qinghao(Artemisia) regardless of a lot of mentioning of its name Qinghao in those literatures. All species in Qinghao(Artemisia) family were mixed and by the time of 1970’s two of Qinghao(Artemisia) species were collected in Chinese Pharmacopoeis and four others were also being prescribed.

Our subsequent investigation proved that only Artemisia annua L contains artemisinin and is effective against malaria.

In addition to the confusion in the selection of right species and the difficulty caused by the low content of artemisinin in the herb, variouables such as the meicinal part of the plant, the growing regions, the harvest season, and extraction/purificaiton processes, etc, added extra difficulties in the discovery of artemisinin. Success in identifying effectiveness of Qinghao neutral ether extract is not a simple and easy win.

No doubt, traditional Chinese medicine provides a rich resource. Nevertheless, it requires our thoughtful consideration to explore and improve.

Persistency in front of Challenges

Research condition was relatively poor in China in the 1970s. In order to produce sufficient quantity of Qinghao extract for clinical trial, the team carried out extraction using several household water wats. Some members’ health was deteriorated due to exposure to a large quantity of organic solvent and insufficient ventilation equipment. In order to launch clinical trial sooner while not compromising patient safety, based on the limited safety data from the animal study, the team members and myself volunteered to take Qinhhao extract ourselves to assure its safety.

Unsatisfied results were observed in the clinical trial using artemisinin tablets, the team carried out a thorough investigation and verified poor disintegration of the tablets as the root course which allowed us to quickly resume the trials using capsules and confirm artemisinin’s clinical efficacy in time.

Collaborative Team Efforts Expedited Translation from Scientific Discovery to Effective Medicine

An antimalarial drug research symposium was held by the national project 523 office in Nanjing on 8th March 1972. In this meeting, on behalf of the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica. I reported the positive readouts of the Qinghao extract No. 191 observed in animal studies performed on malaria mice and monkeys. The presentation received significant interests. On 17th November 1972, I reported the results of successful treatment of thirty clinical cases in the national conference held in Beijing. This triggered a naitonwide conllaboration in research on Qinghao for malaria treatment.

Today, I would like to express my sincere appreciation again to my fellow project 523 colleagues in the Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine for their devotion and exceptional contributions during discovery and subsequent applicaiton of artemisinin. I would like to, once again, thank and congratulate the colleagues from Shandong Provincial institute of Chinese Medicine, Yunnan Provincial Institute of Materia Medica, the Institute of Biophysics of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry of Chinese Medicine, Academy of Military Medical Sciences and many other institutes for their invaluable contribution in their respective responsible areas during collaboration and their helps to and care for the malaria patients. I would also like to express my sincere respect to the mational 523 office leadership team for their continuous efforts in organizing and coordinating the antimalarial research programs. Without collective efforts, we would not be able to present artemisinin-our gift to the world in such a short period of time.

Malaria Remain as a Severe Challenge to the Global Public Health

”The findings in this year’s World Malaria Report demonstrate that the world is continuing to make impressive progress in reducing malaria cases and deaths”. Dr. Margaret Chan, Director-General of World Health Organization commented in the recent World Malaria Report. Nevertheless, statisically, there are approximately 3.3 billions of population across 97 countries or regions still at a risk of malaria contraction and around 1.2billion people live in the high risk regions where the infection rate is as high as or over 1/1000. According to the latest statisitical estimation, approximately 198 million cases of malaria occurred globally in 2013 whih caused 580.000 deaths with 90% from severely affected African countries and 78% being children below age five. Only 70% of malaria patients receive artemisinin combinaiton therapies (ACTs) inAfrica an as high as 56 millions to 69 millions of child malaria patients do not have ACTs available for them.

The Severe Warning of Parasites Resistant to Artemisinin

This slide shows the areas where artemisinin resistant malaria appears according to this year’s report. Artemisinin resistant P. Falciparum has been detect in the areas highlighted in red and black. Clearly, this is a severe warning since the resistance to artemisinin is not only detected in the Greater Mekong sub-region but also appreas in some of African regions.

Global Plan for Artemisinin Resistance Containment

The goal of the Global Plan for Artemisinin Resistant Containment (GPARC) is to protect ACTs as an effective treatment for P. Falciparum malaria. Artemisinin resistance has been confirmed within the Greater Mekong sub-region, and potential epidemic risk is under a critical review. An unanimous agreement has been reached by over hundred experts involved in the program that the chance of containing and eradicating artemisinin resistant malaria is very limited and there is an urgent need to constrain artemisinin resistance.

To protect efficacy of ACT, I strongly urge a global compliance to the GPARC. This is our responsibility as a scientist and medical doctor in the field.

WHO Global Plan for Arteminsinin Resistant Containment, 2011.

Chinese Medicine, A Great Treasure

Before I conclude today’s lecture, I would like to discuss brieflly about Chinese medicine.”Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure-house. We should explore them and raise them to a higher level”. Artemisinin was explored from this resource. From research experience in artemisinin discovery, we learnt strengths from both Chinese and Western medicines. There are a great potential and future advance if these strengths can be fully integrated. We have a substantial amount of natural resource from which our fellow medical researchers can develop novel medicines. ” Since ”tasting hundred herbs by Shen Nong”, we have accumulated substantial experience in clinical practice, integrated and summarised medical application of most nature resource over last thousands of years through Chinese medicine. Adopting, exploring, developing and advancing these practices would allow us to discover more novel medicines beneficial to the world healthcare.

On the Stork Tower

To end my talk, I would like to share with you the well-known poem, ”On the stork tower”. Of Tang Dynasty

On the stork tower1

The sun along the mountain bows;

The Yellow River seawards flows;

You will enjoy a grander sight,

By climbing to a greater height.

Let’s reach to a greater height to appreciate Chinese culture and find the beauty and treasure in the territory of traditional Chinese medicine!

Acknowledgements

Finally, I would like to acknowledge all colleagues in China and overseas for their contributions in the discovery, research and clinical application of artemisinin!

I am deeply grateful for all my family members for their continuous understanding and support!

I sincerely appreciate your kind attention!

Thank you all!

(Source, www.nobelprize.org, Nobel Media)

Editor: Xuefei Chen Axelssson

Chinese version: 中文版如下:屠呦呦诺奖演讲:青蒿素-中医药给世界的一份礼物。

12月7日下午中国首位诺贝尔生理学或医学奖得主屠呦呦在瑞典卡罗林斯卡医学院发表演讲,介绍了自己获奖的科研成果。演讲全文如下:

尊敬的主席先生,尊敬的获奖者,女士们,先生们:

今天我极为荣幸能在卡罗林斯卡学院讲演,我报告的题目是:青蒿素——中医药给世界的一份礼物。

在报告之前,我首先要感谢诺贝尔奖评委会,诺贝尔奖基金会授予我2015年生理学或医学奖。这不仅是授予我个人的荣誉,也是对全体中国科学家团队的嘉奖和鼓励。在短短的几天里,我深深地感受到了瑞典人民的热情,在此我一并表示感谢。

谢谢William C. Campbell(威廉姆.坎贝尔)和Satoshi Ōmura(大村智)二位刚刚所做的精彩报告。我现在要说的是四十年前,在艰苦的环境下,中国科学家努力奋斗从中医药中寻找抗疟新药的故事。

关于青蒿素的发现过程,大家可能已经在很多报道中看到过。在此,我只做一个概要的介绍。这是中医研究院抗疟药研究团队当年的简要工作总结,其中蓝底标示的是本院团队完成的工作,白底标示的是全国其他协作团队完成的工作。 蓝底向白底过渡标示既有本院也有协作单位参加的工作。

中药研究所团队于1969年开始抗疟中药研究。经过大量的反复筛选工作后,1971年起工作重点集中于中药青蒿。又经过很多次失败后,1971年9月,重新设计了提取方法,改用低温提取,用乙醚回流或冷浸,而后用碱溶液除掉酸性部位的方法制备样品。1971年10月4日,青蒿乙醚中性提取物,即标号191#的样品,以1.0克/公斤体重的剂量,连续3天,口服给药,鼠疟药效评价显示抑制率达到100%。同年12月到次年1月的猴疟实验,也得到了抑制率100% 的结果。青蒿乙醚中性提取物抗疟药效的突破,是发现青蒿素的关键。

1972年8至10月,我们开展了青蒿乙醚中性提取物的临床研究,30例恶性疟和间日疟病人全部显效。同年11月,从该部位中成功分离得到抗疟有效单体化合物的结晶,后命名为“青蒿素”。

1972年12月开始对青蒿素的化学结构进行探索,通过元素分析、光谱测定、质谱及旋光分析等技术手段,确定化合物分子式为C15H22O5,分子量282。明确了青蒿素为不含氮的倍半萜类化合物。

1973年4月27日,经中国医学科学院药物研究所分析化学室进一步复核了分子式等有关数据。1974年起,与中国科学院上海有机化学研究所和生物物理所相继开展了青蒿素结构协作研究的工作。最终经X光衍射确定了青蒿素的结构。确认青蒿素是含有过氧基的新型倍半萜内酯。立体结构于1977年在中国的科学通报发表,并被化学文摘收录。

1973年起,为研究青蒿素结构中的功能基团而制备衍生物。经硼氢化钠还原反应,证实青蒿素结构中羰基的存在,发明了双氢青蒿素。经构效关系研究:明确青蒿素结构中的过氧基团是抗疟活性基团,部分双氢青蒿素羟基衍生物的鼠疟效价也有所提高。

这里展示了青蒿素及其衍生物双氢青蒿素、蒿甲醚、青蒿琥酯、蒿乙醚的分子结构。直到现在,除此类型之外,其他结构类型的青蒿素衍生物还没有用于临床的报道。

1986年,青蒿素获得了卫生部新药证书。于1992年再获得双氢青蒿素新药证书。该药临床药效高于青蒿素10倍,进一步体现了青蒿素类药物“高效、速效、低毒”的特点。

1981年,世界卫生组织、世界银行、联合国计划开发署在北京联合召开疟疾化疗科学工作组第四次会议,有关青蒿素及其临床应用的一系列报告在会上引发热烈反响。我的报告是“青蒿素的化学研究”。上世纪80年代,数千例中国的疟疾患者得到青蒿素及其衍生物的有效治疗。

听完这段介绍,大家可能会觉得这不过是一段普通的药物发现过程。但是,当年从在中国已有两千多年沿用历史的中药青蒿中发掘出青蒿素的历程却相当艰辛。

目标明确、坚持信念是成功的前提。1969年,中医科学院中药研究所参加全国“523”抗击疟疾研究项目。经院领导研究决定,我被指令负责並组建“523”項目课题组,承担抗疟中药的研发。这一项目在当时属于保密的重点军工项目。对于一个年轻科研人员,有机会接受如此重任,我体会到了国家对我的信任,深感责任重大,任务艰巨。我决心不辱使命,努力拼搏,尽全力完成任务!

学科交叉为研究发现成功提供了准备。这是我刚到中药研究所的照片,左侧是著名生药学家楼之岑,他指导我鉴别药材。从1959年到1962年,我参加西医学习中医班,系统学习了中医药知识。化学家路易˙帕斯特说过“机会垂青有准备的人”。古语说:凡是过去,皆为序曲。然而,序曲就是一种准备。当抗疟项目给我机遇的时候,西学中的序曲为我从事青蒿素研究提供了良好的准备。

信息收集、准确解析是研究发现成功的基础。接受任务后,我收集整理历代中医药典籍,走访名老中医并收集他们用于防治疟疾的方剂和中药、同时调阅大量民间方药。在汇集了包括植物、动物、矿物等2000余内服、外用方药的基础上,编写了以640种中药为主的《疟疾单验方集》。正是这些信息的收集和解析铸就了青蒿素发现的基础,也是中药新药研究有别于一般植物药研发的地方。

关键的文献启示。当年我面临研究困境时,又重新温习中医古籍,进一步思考东晋(公元3-4世纪)葛洪《肘后备急方》有关“青蒿一握,以水二升渍,绞取汁,尽服之”的截疟记载。这使我联想到提取过程可能需要避免高温,由此改用低沸点溶剂的提取方法。

关于青蒿入药,最早见于马王堆三号汉墓的帛书《五十二病方》,其后的《神农本草经》、《补遗雷公炮制便览》、《本草纲目》等典籍都有青蒿治病的记载。然而,古籍虽多,确都没有明确青蒿的植物分类品种。当年青蒿资源品种混乱,药典收载了2个品种,还有4个其他的混淆品种也在使用。后续深入研究发现:仅Artemisia annua L.一种含有青蒿素,抗疟有效。这样客观上就增加了发现青蒿素的难度。再加上青蒿素在原植物中含量并不高,还有药用部位、产地、采收季节、纯化工艺的影响,青蒿乙醚中性提取物的成功确实来之不易。中国传统中医药是一个丰富的宝藏,值得我们多加思考,发掘提高。

在困境面前需要坚持不懈。七十年代中国的科研条件比较差,为供应足够的青蒿有效部位用于临床,我们曾用水缸作为提取容器。由于缺乏通风设备,又接触大量有机溶剂,导致一些科研人员的身体健康受到了影响。为了尽快上临床,在动物安全性评价的基础上,我和科研团队成员自身服用有效部位提取物,以确保临床病人的安全。当青蒿素片剂临床试用效果不理想时,经过努力坚持,深入探究原因,最终查明是崩解度的问题。改用青蒿素单体胶囊,从而及时证实了青蒿素的抗疟疗效。

团队精神,无私合作加速科学发现转化成有效药物。1972年3月8日,全国523办公室在南京召开抗疟药物专业会议,我代表中药所在会上报告了青蒿No.191提取物对鼠疟、猴疟的结果,受到会议极大关注。同年11月17日,在北京召开的全国会议上,我报告了30例临床全部显效的结果。从此,拉开了青蒿抗疟研究全国大协作的序幕。

今天,我再次衷心感谢当年从事523抗疟研究的中医科学院团队全体成员,铭记他们在青蒿素研究、发现与应用中的积极投入与突出贡献。感谢全国523项目单位的通力协作,包括山东省中药研究所、云南省药物研究所、中国科学院生物物理所、中国科学院上海有机所、广州中医药大学以及军事医学科学院等,我衷心祝贺协作单位同行们所取得的多方面成果,以及对疟疾患者的热诚服务。对于全国523办公室在组织抗疟项目中的不懈努力,在此表示诚挚的敬意。没有大家无私合作的团队精神,我们不可能在短期内将青蒿素贡献给世界。

疟疾对于世界公共卫生依然是个严重挑战。WHO总干事陈冯富珍在谈到控制疟疾时有过这样的评价,在减少疟疾病例与死亡方面,全球范围内正在取得的成绩给我们留下了深刻印象。虽然如此,据统计,全球97个国家与地区的33亿人口仍在遭遇疟疾的威胁,其中12亿人生活在高危区域,这些区域的患病率有可能高于1/1000。统计数据表明,2013年全球疟疾患者约为1亿9千8百万,疟疾导致的死亡人数约为58万,其中78%是5岁以下的儿童。90%的疟疾死亡病例发生在重灾区非洲。70% 的非洲疟疾患者应用青蒿素复方药物治疗(Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies, ACTs)。但是,得不到ACTs 治疗的疟疾患儿仍达5千6百万到6千9百万之多。

疟原虫对于青蒿素和其他抗疟药的抗药性。在大湄公河地区,包括柬埔寨、老挝、缅甸、泰国和越南,恶性疟原虫已经出现对于青蒿素的抗药性。在柬埔寨-泰国边境的许多地区,恶性疟原虫已经对绝大多数抗疟药产生抗药性。请看今年报告的对于青蒿素抗药性的分布图,红色与黑色提示当地的恶性疟原虫出现抗药性。可见,不仅在大湄公河流域有抗药性,在非洲少数地区也出现了抗药性。这些情况都是严重的警示。

世界卫生组织2011年遏制青蒿素抗药性的全球计划。这项计划出台的目的是保护ACTs对于恶性疟疾的有效性。鉴于青蒿素的抗药性已在大湄公河流域得到证实,扩散的潜在威胁也正在考察之中。参与该计划的100多位专家们认为,在青蒿素抗药性传播到高感染地区之前,遏制或消除抗药性的机会其实十分有限。遏制青蒿素抗药性的任务迫在眉睫。为保护ACTs对于恶性疟疾的有效性,我诚挚希望全球抗疟工作者认真执行WHO遏制青蒿素抗药性的全球计划。

在结束之前,我想再谈一点中医药。“中国医药学是一个伟大宝库,应当努力发掘,加以提高。”青蒿素正是从这一宝库中发掘出来的。通过抗疟药青蒿素的研究经历,深感中西医药各有所长,二者有机结合,优势互补,当具有更大的开发潜力和良好的发展前景。大自然给我们提供了大量的植物资源,医药学研究者可以从中开发新药。中医药从神农尝百草开始,在几千年的发展中积累了大量临床经验,对于自然资源的药用价值已经有所整理归纳。通过继承发扬,发掘提高,一定会有所发现,有所创新,从而造福人类。

最后,我想与各位分享一首我国唐代有名的诗篇,王之涣所写的《登鹳雀楼》:白日依山尽,黄河入海流,欲穷千里目,更上一层楼。 请各位有机会时更上一层楼, 去领略中国文化的魅力,发现蕴涵于传统中医药中的宝藏!

衷心感谢在青蒿素发现、研究、和应用中做出贡献的所有国内外同事们、同行们和朋友们!

深深感谢家人的一直以来的理解和支持!

衷心感谢各位前来参会!

谢谢大家!

By Xuefei Chen Axelsson

STOCKHOLM, Dec. 11(Greenpost)–Chinese scientist Tu Youyou has received her Nobel Prize Diploma from the hands of the Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf in Stockholm Concert Hall.

Professor Hans Forssberg explained the great achievement made by Tu Youyou.

“During the 1960s and 70s, Tu Youyou took part in a major Chinese project to develop anti-malarial drugs. When Tu studied ancient literature, she found that the plant Artemisia annua or sweet wormwood, recurred in various recipes against fever.”

She tested an extract from the plant on infected mice. Some of the malaria parasites died, but the effect varied.

So Tu returned to the Literature, and in a 1700-year-old book she found a method for obtaining the extract without heating up the plant. The resulting extract was extremely potent and killed all the parasites.

The active component was identified and given the name Artemisinin.

It turned out that Artemisinin attacks the malaria in a unique way.

The discovery of Artemisinin has led to development of a new drug that has saved the lives of millions of people,halving the mortality rate of malaria during the past 15 years.

“Your discoveries represent a paradigm shift in medicine, which has not only provided revolutionary therapies for patients suffering from devastating parasitic diseases, but also promoted well-being and prosperity for individuals an society. The global impact of your discoveries and the resulting benefit to mankind are immeasurable. ”

Tu Youyou was the first Chinese women scientist who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

Tu Youyou was the first Chinese women scientist who won the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

From Nobelprize.org.

She also participated in the Nobel dinner with her husband Li Tingzhao, daughter and grand daughter.

Photo/Xinhua

BANGKOK, Dec. 3 (Greenpost) — China and Thailand signed an intergovernmental framework document on railway cooperation here on Thursday, which serves as an important basis for future efforts to push forward the railway project.

The foundational document for the bilateral cooperation in constructing an 867-kilometer medium-speed railway line in Thailand was signed by Thai Transport Minister Arkhom Termpittayapaisith and deputy head of China’s National Development and Reform Commission Wang Xiaotao.

The signing ceremony was held at the ninth meeting of the Joint Committee on Railway Cooperation between the Thailand and China.

According to the document, the railway project, a dual-track line which uses 1.435-meter standard gauge with trains operating at top speeds of 160-180 kph, will be implemented in the form of EPC (engineering, procurement, construction), according to Chinese negotiators.

A joint venture will be set up in charge of part of the investment and railway operation, the statement said, adding the Chinese side will support Thailand in terms of technology licensing and transfer, human resources training, and financing.

A foundation stone laying ceremony for the railway project will be held later this month. Both sides are striving to speed up the process so that construction could start in May next year.

The railway project will significantly enhance connectivity between Thailand and China and boost economic growth in Thailand, especially in its northeastern part, according to the statement.

As an important part of the trans-Asian railway network, the project will potentially reinforce Thailand’s position as a transport hub in the region and inject vitality into the economic development in the southwestern part of China.

In addition to the railway document, a contract was signed by the China National Cereals, Oils and Foodstuffs Corporation and the Foreign Trade Department of the Commerce Ministry of Thailand, under which the Chinese enterprise will purchase 1 million tons of newly-harvested rice from Thailand.

China’s Sinochem and the Rubber Authority of Thailand also inked a purchase agreement, under which Thailand will sell 200,000 tons of natural rubber to the Chinese company.

The purchases will help propel the growth of the two countries’ economic and trade ties while further promoting Thailand’s rubber products in China and other major markets, the statement said. Enditem

Source Xinhua

北欧绿色邮报网报道(记者陈雪霏)--诺贝尔和平奖颁奖仪式10日在挪威首都奥斯陆举行。

突尼斯“全国对话四方大会”获得颁奖。颁奖理由是为他们的和解和对话。

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wv6veGSCqw

By Xuefei Chen Axelsson

Stockholm, Dec. (Greenpost)–The awaiting Nobel Prize awarding ceremony is scheduled to take place in Stockholm Concert Hall at 16:30 Stockholm local time .

Tu Youyou and her counterparts in medicine and two physics laureates, three chemistry laureates and one laureate in literature as well as on laureate in economics will receive their Nobel Prize from the hands of the Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf.

Tu Youyou and her counterparts in medicine and two physics laureates, three chemistry laureates and one laureate in literature as well as on laureate in economics will receive their Nobel Prize from the hands of the Swedish King Carl XVI Gustaf.

A grand banquet will be held at 19:00 in the Stockholm City Hall.

During the week, Chinese Nobel winner in Medicine Tu Youyou has attended a press conference to answer the journalists questions, given Nobel lectures and today she will attend the awarding ceremony and the banquet.

During the week, Chinese Nobel winner in Medicine Tu Youyou has attended a press conference to answer the journalists questions, given Nobel lectures and today she will attend the awarding ceremony and the banquet.

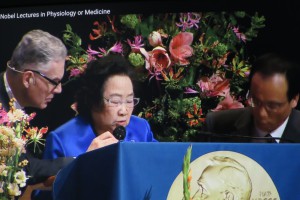

Tu Youyou gave Nobel Lecture in Chinese at Karolinska Institute.

Left, Jan Andersson. middle, Tu Youyou and right, interpretor.

Photo by Xuefei Chen Axelsson from live screen on Dec. 7, 2015.

By Xuefei Chen Axelsson

Stockholm, Oct. 5(Greenpost)– Greenpost has interviewed Jan Andersson, Nobel Assembly Member and Professor at Infectious Disease Department of Karolinska Institute in Huddinge. The following is the text of the interview:

Filmed by Anneli Larsson on Oct. 5, 2015 at Nobel Forum.

Hello I am Xuefei Chen Axelsson, I am in the Nobel Forum and we just had the press conference about this year’s Nobel Prize in Medicine, and Chinese Tu Youyou won the prize, so here we have the expert(Nobel Assembly Member Jan Andersson) explain this.

Xuefei Chen Axelsson: So can you tell us why Tu Youyou wins this prize?

Jan Andersson: So Youyou Tu got half of this Nobel Prize for her discovery of Arteminsinen. And she did that from a herb, so she was the one who identified that Artemisinin annua herb, the Chinese Artemisinin branch contains compound Artemisinin that actually has the best effect against Malaria Parasite that has ever been found. So she discovered a way to elute out the active compound from the herb. She also discovered how to elute away the toxic compartments from the herb, so actually it could be developed a safe and very efficacy drug Artemisinin for the treatment of severe Malaria.

Chen Axelsson: How do you comment the contribution of this discovery?

Chen Axelsson: How do you comment the contribution of this discovery?

Jan Andersson: Her component to identify how to elute out the biological activity or type of compound that was, how to purify it and then make it crystals and identification of molecular formulation for that, she set the stage for this whole development. It was a team effort, but she did the paradigm shift, the shift that open the doors for other scientist to go about, to contribute to the further development. She went in this process. It was a national process, when there were some success, but there were also failures, and they were wondering which way to go. There was a part of the projects that look for all types of traditional Chinese medicine, to see whether you can find something there.

And she went in then with knowledge of chemistry and pharmacy in how to elude out things, how to isolate things and how to test them for biological activity, and that was really a paradigm shift. She made the change to our knowledge. Then after she had identified this biological compound, and it was safe, and has got rid of the toxicity, then there was a lot of other groups in China who took this further on, to try it in different animal models, and then try it more on human infected with malaria, and then eventually there was companies that took on large scale production. But you know there is always someone to lead, and we were very happy when we saw who that was and we could identify down to Youyou Tu in specific moments in her career when she did it.

Chen Axelsson: And can we say that if without this medicine, we would have millions millions of people lost their lives.

Jan Andersson: Yes, we can say that because there was clinical trials done later on with pure substance of Artemisinin. The pure substance of Artemisinin was tested against conventional chimin Mefluquin, and it was demonstrated significant reduce mortality….30 percent reduction of mortality in children below age of five with severe malaria. So we can say that at least a hundred thousand lives are saved every year by that. We can also say that the total morbidity illness goes down because there is completely new medicinic action so that Artemisinin involves much earlier on in the life cycle of the disease.

Chen Axelsson: It’s like vaccination?

Jan Andersson: No, you cannot say it’s vaccination, it is a cure. And we do not use it for prevention. We keep it for the cure of the infected ill people.

Chen Axelsson: Maybe briefly talk about the other half of the prize?

Jan Andersson: Yes, the other half goes to scientist in Japan, Satoshi Ömura and then his collabrator in the United States, William Campbell, together, they collectively discovered a new compound for treatment of roundworm infections, calling them in Latin Namatom infections, they infect a third of the human population, and generate chronic worm infections. There are two examples of that, quite well-known, river blindness and elephantiasis, those affected 25 million who get river blindness infection and you get 120 million who have elephantiasis, they are called filariasis. And they discovered the compound that by single yearly doze cure if you repeat in a number of years because it kills the microfilaria, the small children or the adult filaria extremely effective with single doses in 12 months.

This are predominantly affecting Africa, but there are also in Americas and South East Asia, Asia like Yemen that has problems for that. Predominantly in Sub-Sahara Africa. River Blindness in 31 nations, and elephantiasis in 81 nations affected by this disease.

Campbell was born in Ireland and lived in America. Ömora screened the bacteria, he screened 45 thousand bacteria, and then he selected 50 that he gave to Campbell. And Campbell has specific means eluting out biological activity against numbers of different microbs. And he discovered the novel theraphy against infections caused by roundworm parasites.

Xuefei Chen Axelsson: Thank you very much!

By Xuefei Chen Axelsson

Stockholm, Dec. 7(Greenpost)– Nobel Laureate in Literature Svetlana Alexievich Monday gave a very sad yet very striking speech titled On the Battle Lost at Swedish Academy for her Nobel lecture.

Alexivich signed her signature in the back of a chair at Nobel Museum on Dec. 6. Photo Alexander Muhamoud.

From the very first paragraph, she began to use her novel style to quote the interviewees words to express what kind of people as a Russian, a Belarussian and even Ukrain is like.

” I grew up in the countryside. As children, we loved to play outdoors, but come evening, the voices of tired village women who gathered on benches near their cottages drew us like magnets. None of them had husbands, fathers or brothers.I don’t remember men in our village after World War II: during the war, one out of four Belarussians perished, either fighting at the front or with the partisans.”

Just with a couple of sentences she has summerised about her background.

“After the war, we children lived in a world of women. What I remember most, is that women talked about love, not death. They would tell stories about saying goodbye to the men they loved the day before they went to war, they would talk about waiting for them, and how they were still waiting. Years had passed, but they continued to wait: “I don’t care if he lost his arms and legs, I’ll carry him.” No arms … no legs … I think I’ve known what love is since childhood …”

Then she directly quoted her interviews which present people in front and let the people say.

First voice:

“Why do you want to know all this? It’s so sad. I met my husband during the war. I was in a tank crew that made it all the way to Berlin. I remember, we were standing near the Reichstag – he wasn’t my husband yet – and he says to me: “Let’s get married. I love you.” I was so upset – we’d been living in filth, dirt, and blood the whole war, heard nothing but obscenities. I answered: “First make a woman of me: give me flowers, whisper sweet nothings. When I’m demobilized, I’ll make myself a dress.” I was so upset I wanted to hit him. He felt all of it. One of his cheeks had been badly burned, it was scarred over, and I saw tears running down the scars. “Alright, I’ll marry you,” I said. Just like that … I couldn’t believe I said it … All around us there was nothing but ashes and smashed bricks, in short – war.”

Second voice:

“We lived near the Chernobyl nuclear plant. I was working at a bakery, making pasties. My husband was a fireman. We had just gotten married, and we held hands even when we went to the store. The day the reactor exploded, my husband was on duty at the firе station. They responded to the call in their shirtsleeves, in regular clothes – there was an explosion at the nuclear power station, but they weren’t given any special clothing. That’s just the way we lived … You know … They worked all night putting out the fire, and received doses of radiation incompatible with life. The next morning they were flown straight to Moscow. Severe radiation sickness … you don’t live for more than a few weeks … My husband was strong, an athlete, and he was the last to die. When I got to Moscow, they told me that he was in a special isolation chamber and no one was allowed in. “But I love him,” I begged. “Soldiers are taking care of them. Where do you think you’re going?” “I love him.” They argued with me: “This isn’t the man you love anymore, he’s an object requiring decontamination. You get it?” I kept telling myself the same thing over and over: I love, I love … At night, I would climb up the fire escape to see him … Or I’d ask the night janitors … I paid them money so they’d let me in … I didn’t abandon him, I was with him until the end … A few months after his death, I gave birth to a little girl, but she lived only a few days. She … We were so excited about her, and I killed her … She saved me, she absorbed all the radiation herself. She was so little … teeny-tiny … But I loved them both. How can love be killed? Why are love and death so close? They always come together. Who can explain it? At the grave I go down on my knees …”

Third Voice:

“The first time I killed a German … I was ten years old, and the partisans were already taking me on missions. This German was lying on the ground, wounded … I was told to take his pistol. I ran over, and he clutched the pistol with two hands and was aiming it at my face. But he didn’t manage to fire first, I did …

It didn’t scare me to kill someone … And I never thought about him during the war. A lot of people were killed, we lived among the dead. I was surprised when I suddenly had a dream about that German many years later. It came out of the blue … I kept dreaming the same thing over and over … I would be flying, and he wouldn’t let me go. Lifting off … flying, flying … He catches up, and I fall down with him. I fall into some sort of pit. Or, I want to get up … stand up … But he won’t let me … Because of him, I can’t fly away …

The same dream … It haunted me for decades …

Alexievich has a deep reflection about Russian or socialist history and culture.

“I lived in a country where dying was taught to us from childhood. We were taught death. We were told that human beings exist in order to give everything they have, to burn out, to sacrifice themselves. We were taught to love people with weapons. Had I grown up in a different country, I couldn’t have traveled this path. Evil is cruel, you have to be inoculated against it. We grew up among executioners and victims. Even if our parents lived in fear and didn’t tell us everything – and more often than not they told us nothing – the very air of our life was poisoned. Evil kept a watchful eye on us.

I have written five books, but I feel that they are all one book. A book about the history of a utopia …”

According to her reflection, it seems to me that the communist idea is so deep in the Russian federation that it broke.

Please read yourself for the following and draw your own conclusion.

Twenty years ago, we bid farewell to the “Red Empire” of the Soviets with curses and tears. We can now look at that past more calmly, as an historical experiment. This is important, because arguments about socialism have not died down. A new generation has grown up with a different picture of the world, but many young people are reading Marx and Lenin again. In Russian towns there are new museums dedicated to Stalin, and new monuments have been erected to him.

The “Red Empire” is gone, but the “Red Man,” homo sovieticus, remains. He endures.

My father died recently. He believed in communism to the end. He kept his party membership card. I can’t bring myself to use the word ‘sovok,’ that derogatory epithet for the Soviet mentality, because then I would have to apply it my father and others close to me, my friends. They all come from the same place – socialism. There are many idealists among them. Romantics. Today they are sometimes called slavery romantics. Slaves of utopia. I believe that all of them could have lived different lives, but they lived Soviet lives. Why? I searched for the answer to that question for a long time – I traveled all over the vast country once called the USSR, and recorded thousands of tapes. It was socialism, and it was simply our life. I have collected the history of “domestic,” “indoor” socialism, bit by bit. The history of how it played out in the human soul. I am drawn to that small space called a human being … a single individual. In reality, that is where everything happens.

Right after the war, Theodor Adorno wrote, in shock: “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” My teacher, Ales Adamovich, whose name I mention today with gratitude, felt that writing prose about the nightmares of the 20th century was sacrilege. Nothing may be invented. You must give the truth as it is. A “super-literature” is required. The witness must speak. Nietzsche’s words come to mind – no artist can live up to reality. He can’t lift it.

It always troubled me that the truth doesn’t fit into one heart, into one mind, that truth is somehow splintered. There’s a lot of it, it is varied, and it is strewn about the world. Dostoevsky thought that humanity knows much, much more about itself than it has recorded in literature. So what is it that I do? I collect the everyday life of feelings, thoughts, and words. I collect the life of my time. I’m interested in the history of the soul. The everyday life of the soul, the things that the big picture of history usually omits, or disdains. I work with missing history. I am often told, even now, that what I write isn’t literature, it’s a document. What is literature today? Who can answer that question? We live faster than ever before. Content ruptures form. Breaks and changes it. Everything overflows its banks: music, painting – even words in documents escape the boundaries of the document. There are no borders between fact and fabrication, one flows into the other. Witnessеs are not impartial. In telling a story, humans create, they wrestle time like a sculptor does marble. They are actors and creators.

I’m interested in little people. The little, great people, is how I would put it, because suffering expands people. In my books these people tell their own, little histories, and big history is told along the way. We haven’t had time to comprehend what already has and is still happening to us, we just need to say it. To begin with, we must at least articulate what happened. We are afraid of doing that, we’re not up to coping with our past. In Dostoevsky’sDemons, Shatov says to Stavrogin at the beginning of their conversation: “We are two creatures who have met in boundless infinity … for the last time in the world. So drop that tone and speak like a human being. At least once, speak with a human voice.”

That is more or less how my conversations with my protagonists begin. People speak from their own time, of course, they can’t speak out of a void. But it is difficult to reach the human soul, the path is littered with television and newspapers, and the superstitions of the century, its biases, its deceptions.

I would like to read a few pages from my diaries to show how time moved … how the idea died … How I followed in its path …

I’m writing a book about the war … Why about the war? Because we are people of war – we have always been at war or been preparing for war. If one looks closely, we all think in terms of war. At home, on the street. That’s why human life is so cheap in this country. Everything is wartime.

I began with doubts. Another book about World War II … What for?

On one trip I met a woman who had been a medic during the war. She told me a story: as they crossed Lake Ladoga during the winter, the enemy noticed some movement and began to shoot at them. Horses and people fell under the ice. It all happened at night. She grabbed someone she thought was injured and began to drag him toward the shore. “I pulled him, he was wet and naked, I thought his clothes had been torn off,” she told me. Once on shore, she discovered that she had been dragging an enormous wounded sturgeon. And she let loose a terrible string of obscenities: people are suffering, but animals, birds, fish – what did they do? On another trip I heard the story of a medic from a cavalry squadron. During a battle she pulled a wounded soldier into a shell crater, and only then noticed that he was a German. His leg was broken and he was bleeding. He was the enemy! What to do? Her own guys were dying up above! But she bandaged the German and crawled out again. She dragged in a Russian soldier who had lost consciousness. When he came to, he wanted to kill the German, and when the German came to, he grabbed a machine gun and wanted to kill the Russian. “I’d slap one of them, and then the other. Our legs were all covered in blood,” she remembered. “The blood was all mixed together.”

This was a war I had never heard about. A woman’s war. It wasn’t about heroes. It wasn’t about one group of people heroically killing another group of people. I remember a frequent female lament: “After the battle, you’d walk through the field. They lay on their backs … All young, so handsome. They lay there, staring at the sky. You felt sorry for all of them, on both sides.” It was this attitude, “all of them, on both sides,” that gave me the idea of what my book would be about: war is nothing more than killing. That’s how it registered in women’s memories. This person had just been smiling, smoking – and now he’s gone. Disappearance was what women talked about most, how quickly everything can turn into nothing during war. Both the human being, and human time. Yes, they had volunteered for the front at 17 or 18, but they didn’t want to kill. And yet – they were ready to die. To die for the Motherland. And to die for Stalin – you can’t erase those words from history.

The book wasn’t published for two years, not before perestroika and Gorbachev. “After reading your book no one will fight,” the censor lectured me. “Your war is terrifying. Why don’t you have any heroes?” I wasn’t looking for heroes. I was writing history through the stories of its unnoticed witnesses and participants. They had never been asked anything. What do people think? We don’t really know what people think about great ideas. Right after a war, a person will tell the story of one war, a few decades later, it’s a different war, of course. Something will change in him, because he has folded his whole life into his memories. His entire self. How he lived during those years, what he read, saw, whom he met. What he believes in. Finally, whether is he happy or not. Documents are living creatures – they change as we change.

I’m absolutely convinced that there will never again be young women like the war-time girls of 1941. This was the high point of the “Red” idea, higher even than the Revolution and Lenin. Their Victory still eclipses the GULAG. I dearly love these women. But you couldn’t talk to them about Stalin, or about the fact that after the war, whole trainloads of the boldest and most outspoken victors were sent straight to Siberia. The rest returned home and kept quiet. Once I heard: “The only time we were free was during the war. At the front.” Suffering is our capital, our natural resource. Not oil or gas – but suffering. It is the only thing we are able to produce consistently. I’m always looking for the answer: why doesn’t our suffering convert into freedom? Is it truly all in vain? Chaadayev was right: Russia is a country without memory, it’s a space of total amnesia, a virgin consciousness for criticism and reflection.

But great books are piled up beneath our feet.

I’m in Kabul. I don’t want to write about war anymore. But here I am in a real war. The newspaper Pravda says: “We are helping the fraternal Afghan people build socialism.” People of war and objects of war are everywhere. Wartime.

They wouldn’t take me into battle yesterday: “Stay in the hotel, young lady. We’ll have to answer for you later.” I’m sitting in the hotel, thinking: there is something immoral in scrutinizing other people’s courage and the risks they take. I’ve been here for two weeks and I can’t shake the feeling that war is a product of masculine nature, which is unfathomable to me. But the everyday accessories of war are grand. I discovered for myself that weapons are beautiful: machine guns, mines, tanks. Man has put a lot of thought into how best to kill other men. The eternal dispute between truth and beauty. They showed me a new Italian mine, and my “feminine” reaction was: “It’s beautiful. Why is it beautiful?” They explained to me precisely, in military terms: if someone drives over or steps on this mine just so … at a certain angle … there would be nothing left but half a bucket of flesh. People talk about abnormal things here as though they’re normal, taken for granted. Well, you know, it’s war … No one is driven insane by these pictures – for instance, there’s a man lying on the ground who was killed not by the elements, not by fate, but by another man.

I watched the loading of a “black tulip” (the airplane that carries casualties back home in zinc coffins). The dead are often dressed in old military uniforms from the ‘40s, with jodhpurs; sometimes there aren’t even enough of those to go around. The soldiers were chatting: “They just delivered some new ones to the fridges. It smells like boar gone bad.” I am going to write about this. I’m afraid that no one at home will believe me. Our newspapers just write about friendship alleys planted by Soviet soldiers.

I talk to the guys. Many have come voluntarily. They asked to come here. I note that most are from educated families, the intelligentsia – teachers, doctors, librarians – in a word, bookish people. They sincerely dreamed of helping the Afghan people build socialism. Now they laugh at themselves. I was shown a place at the airport where hundreds of zinc coffins sparkle mysteriously in the sun. The officer accompanying me couldn’t help himself: “Who knows … my coffin might be over there … They’ll stick me in it … What am I fighting for here?” His own words scared him and he immediately said: “Don’t write that down.”

At night I dream of the dead, they all have looks of surprise on their faces: what, you mean I was killed? Have I really been killed?”

I drove to a hospital for Afghan civilians with a group of nurses – we brought presents for the children. Toys, candy, cookies. I had about five teddy bears. We arrived at the hospital, a long barracks. No one has more than a blanket for bedding. A young Afghan woman approached me, holding a child in her arms. She wanted to say something – over the last ten years almost everyone here has learned to speak a little Russian – and I handed the child a toy, which he took with his teeth. “Why his teeth?” I asked in surprise. She pulled the blanket off his tiny body – the little boy was missing both arms. “It was when your Russians bombed.” Someone held me up as I began to fall.

I saw our “Grad” rockets turn villages into plowed fields. I visited an Afghan cemetery, which was about the length of one of their villages. Somewhere in the middle of the cemetery an old Afghan woman was shouting. I remembered the howl of a mother in a village near Minsk when they carried a zinc coffin into the house. The cry wasn’t human or animal … It resembled what I heard at the Kabul cemetery …

I have to admit that I didn’t become free all at once. I was sincere with my subjects, and they trusted me. Each of us has his or her own path to freedom. Before Afghanistan, I believed in socialism with a human face. I came back from Afghanistan free of all illusions. “Forgive me father,” I said when I saw him. “You raised me to believe in communist ideals, but seeing those young men, recent Soviet schoolboys like the ones you and Mama taught (my parents were village school teachers), kill people they don’t know, on foreign territory, was enough to turn all your words to ash. We are murderers, Papa, do you understand!?” My father cried.

Many people returned free from Afghanistan. But there are other examples, too. There was a young fellow in Afghanistan who shouted to me: “You’re a woman, what do you understand about war? You think that people die a pretty death in war, like they do in books and movies? Yesterday my friend was killed, he took a bullet in the head, and kept running another ten meters, trying to catch his own brains …” Seven years later, the same fellow is a successful businessman, who likes to tell stories about Afghanistan. He called me: “What are your books for? They’re too scary.” He was a different person, no longer the young man I’d met amid death, who didn’t want to die at age twenty …

I ask myself what kind of book I want to write about war. I’d like to write a book about a person who doesn’t shoot, who can’t fire on another human being, who suffers at the very idea of war. Where is he? I haven’t met him.

Russian literature is interesting in that it is the only literature to tell the story of an experiment carried out on a huge country. I am often asked: why do you always write about tragedy? Because that’s how we live. We live in different countries now, but “Red” people are everywhere. They come out of that same life, and have the same memories.

I resisted writing about Chernobyl for a long time. I didn’t know how to write about it, what instrument to use, how to approach the subject. The world had almost never heard anything about my little country, tucked away in a corner of Europe, but now its name was on everyone’s tongue. We, Belarussians, had become the people of Chernobyl. The first to encounter the unknown. It was clear now: besides communist, ethnic, and new religious challenges, there are more global, savage challenges in store for us, though for the moment they are invisible. Something opened a little bit after Chernobyl …

I remember an old taxi driver swearing in despair when a pigeon hit the windshield: “Every day, two or three birds smash into the car. But the newspapers say the situation is under control.”

The leaves in city parks were raked up, taken out of town, and buried. The ground was cut out of contaminated areas and buried, too – earth was buried in the earth. Firewood was buried, and grass. Everyone looked a little crazy. An old beekeeper told me: “I went out into the garden that morning, and something was missing, a familiar sound. There weren’t any bees. I couldn’t hear a single bee. Not a one! What? What’s going on? They didn’t fly out on the second day either, or on the third … Then we were told that there was an accident at the nuclear station – and it isn’t far away. But we didn’t know anything about it for a long time. The bees knew, but we didn’t.” All the information about Chernobyl in the newspapers was in military language: explosion, heroes, soldiers, evacuation … The KGB worked right at the station. They were looking for spies and saboteurs. Rumors circulated that the accident was planned by western intelligence services in order to undermine the socialist camp. Military equipment was on its way to Chernobyl, soldiers were coming. As usual, the system worked like it was war time, but in this new world, a soldier with a shiny new machine gun was a tragic figure. The only thing he could do was absorb large doses of radiation and die when he returned home.

Before my eyes pre-Chernobyl people turned into the people of Chernobyl.

You couldn’t see the radiation, or touch it, or smell it … The world around was both familiar and unfamiliar. When I traveled to the zone, I was told right away: don’t pick the flowers, don’t sit on the grass, don’t drink water from a well … Death hid everywhere, but now it was a different sort of death. Wearing a new mask. In an unfamiliar guise. Old people who had lived through the war were being evacuated again. They looked at the sky: “The sun is shining … There’s no smoke, no gas. No one’s shooting. How can this be war? But we have to become refugees.”

In the mornings everyone would grab the papers, greedy for news, and then put them down in disappointment. No spies had been found. No one wrote about enemies of the people. A world without spies and enemies of the people was also unfamiliar. This was the beginning of something new. Following on the heels of Afghanistan, Chernobyl made us free people.

For me the world parted: inside the zone I didn’t feel Belarussian, or Russian, or Ukrainian, but a representative of a biological species that could be destroyed. Two catastrophes coincided: in the social sphere, the socialist Atlantis was sinking; and on the cosmic – there was Chernobyl. The collapse of the empire upset everyone. People were worried about everyday life. How and with what to buy things? How to survive? What to believe in? What banners to follow this time? Or do we need to learn to live without any great idea? The latter was unfamiliar, too, since no one had ever lived that way. Hundreds of questions faced the “Red” man, but he was on his own. He had never been so alone as in those first days of freedom. I was surrounded by people in shock. I listened to them …

I close my diary …

What happened to us when the empire collapsed? Previously, the world had been divided: there were executioners and victims – that was the GULAG; brothers and sisters – that was the war; the electorate – was part of technology and the contemporary world. Our world had also been divided into those who were imprisoned and those who imprisoned them; today there’s a division between Slavophiles and Westernizers, “fascist-traitors” and patriots. And between those who can buy things and those who can’t. The latter, I would say, was the cruelest of the ordeals to follow socialism, because not so long ago everyone had been equal. The “Red” man wasn’t able to enter the kingdom of freedom he had dreamed of around his kitchen table. Russia was divvied up without him, and he was left with nothing. Humiliated and robbed. Aggressive and dangerous.

Here are some of the comments I heard as I traveled around Russia …

“Modernization will only happen here with sharashkas, those prison camps for scientists, and firing squads.”

“Russians don’t really want to be rich, they’re even afraid of it. What does a Russian want? Just one thing: for no one else to get rich. No richer than he is.”

“There aren’t any honest people here, but there are saintly ones.”

“We’ll never see a generation that hasn’t been flogged; Russians don’t understand freedom, they need the Cossack and the lash.”

“The two most important words in Russian are ‘war’ and ‘prison.’ You steal something, have some fun, they lock you up … you get out, and then end up back in jail …”

“Russian life needs to be vicious and despicable. Then the soul is uplifted, it realizes that it doesn’t belong to this world … The filthier and bloodier things are, the more room there is for the soul …”

“No one has the energy for a new revolution, or the craziness. No spirit. Russians need the kind of idea that will send shivers down your spine …”

“So our life just dangles between bedlam and the barracks. Communism didn’t die, the corpse is still alive.”

I will take the liberty of saying that we missed the chance we had in the 1990s. The question was posed: what kind of country should we have? A strong country, or a worthy one where people can live decently? We chose the former – a strong country. Once again we are living in an era of power. Russians are fighting Ukrainians. Their brothers. My father is Belarussian, my mother, Ukrainian. That’s the way it is for many people. Russian planes are bombing Syria …

A time full of hope has been replaced by a time of fear. The era has turned around and headed back in time. The time we live in now is second-hand …

Sometimes I am not sure that I’ve finished writing the history of the “Red” man …

I have three homes: my Belarussian land, the homeland of my father, where I have lived my whole life; Ukraine, the homeland of my mother, where I was born; and Russia’s great culture, without which I cannot imagine myself. All are very dear to me. But in this day and age it is difficult to talk about love.

Translation: Jamey Gambrell

Jag läste på engelska, tårarna föll och jag kunde inte hålla på.

Jag läste på engelska, tårarna föll och jag kunde inte hålla på.

Det är en ledsen men stark nobelföreläsning. Det är som sin bok. Det är som politiska tal, men det är sentimentallt också. När Xi Jinping och Ma Yingjiu skakade händerna, måste vi tänka att vi är lykliga. Vi kineserna är bröderna också.

Alexievich reflecterade livet så djupt och hon hade tre länderna och hon inte vill se att Ryssland och Belarus slår varandra för att de är bröderna. Men historier passade precis som det är nu.

Jag tycker att det är så ledsen att vi måste tänka om vad man vill.

Jag vill gärna flera människor kan läsa sin nobelföreläsning också.

Var så god.